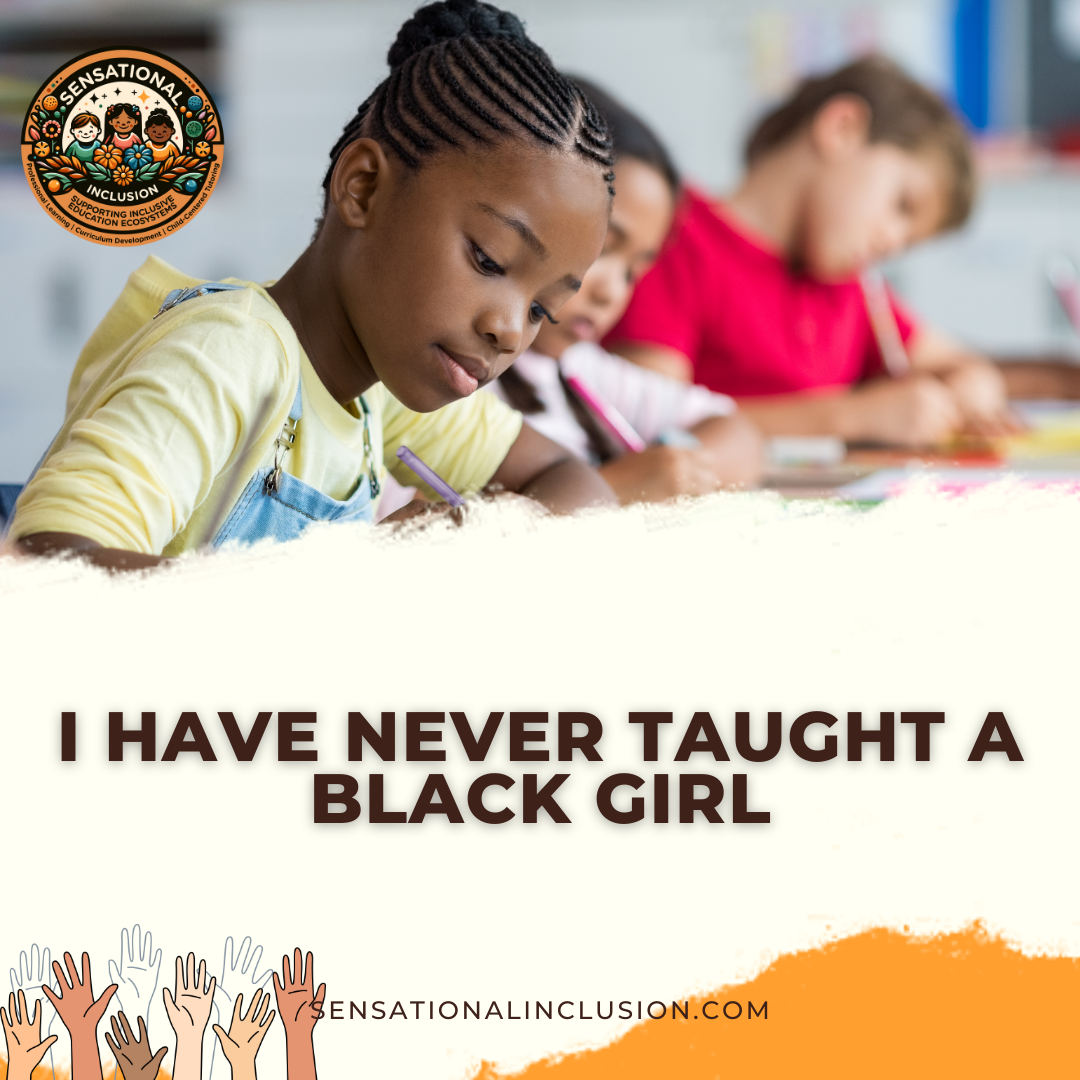

During the first week of second grade, my teacher, Ms. Caulkin, told my mother she was unable to teach me because she had never taught a Black girl. Overhearing this conversation, I remember feeling instantly engulfed in indescribable heat, confusion, and then anger. At seven years old, my anger was misdirected, not towards the anti-Black system and ideologies that created a ‘Ms. Caulkin’ archetype, but at myself. For years, I hated being a Black girl and remember thinking that being Black was the worst thing a kid could be. As I progressed from grade to grade, my experiences in a predominantly white elementary school intensified my feelings of anti-Blackness. The truth is, my teacher’s words hurt deeply, splitting me down the middle. In the following years, school became a spiritless place.

Spirit Murdering: Racism’s Deep Roots in Schools

The impact of Ms. Caulkin’s words was a form of ‘spirit murdering,’ a term Dr. Bettina Love uses to describe the psychological and emotional damage inflicted on Black and Brown students by constant exposure to racism and discrimination. That day, as a young Black girl overhearing her words, I felt a part of my spirit fade away. It was more than a comment; it was a systemic dismissal of my identity and genius. This wasn’t just about one teacher’s ignorance; it reflected a deeper, more malignant issue within our educational system. For me, it highlighted the urgent need to dismantle these oppressive structures and to create educational environments where the lives and experiences of all students are not only recognized but honored as worthy and valid.

Is Ms. Caulkin Really at Fault? Reflecting on Systemic Limitations in Education

The short and less complicated answer is no. I don’t have beef with Ms. Caulkin, and I forgave her many years ago. My beef and overall critique go beyond individual educators as it calls for a transformation at the highest levels of educational governance, demanding a complete overhaul of curricula, teacher training, and institutional policies to create an equitable, inclusive learning environment for all students. Thus, it’s not actually about condemning Ms. Caulkin as an individual but rather focusing our critical lens on the societal and systemic structures that perpetuate such limitations and biases in education.

But That Was 30 Years Ago, Things Have Changed

My dissertation, completed last spring, was a study that focused on the lived experiences of eleven Black girls ages 5-9 in a predominantly white school, revealing what I experienced thirty years ago. The findings were clear and deeply troubling: 10 out of 11 Black girls reported feelings of loneliness, exclusion, and a lack of belonging. Half of them, 5 out of 11, disclosed experiencing suicidal ideation and other mental health concerns. A majority, 9 out of 11 participants, faced violent interactions with peers, and 8 out of 11 recounted violent interactions with teachers.

Over the thirteen weeks of observing their daily school life, I witnessed dozens of incidents that not only validated these reports but also reflected my own past experiences. For example, the suspension of a Black girl for defending herself against racial slurs, the disproportionate reprimanding of Black students for minor infractions, and the overwhelming representation of Black students in special education classes all mirrored my own school days as a Black girl in a similar setting three decades earlier. This parallel highlights a disturbing reality: the mistreatment of Black girls in schools is an enduring issue, not a relic of the past.

Conclusion: A Call to Radical Action

The lesson of Ms. Caulkin goes beyond a singular classroom experience. It’s a clarion call for a radical overhaul of an education system that too often fails its most vulnerable. As educators and change-makers, we must be unafraid to challenge, to dismantle, and to rebuild. Only then can we create educational spaces that truly celebrate and nurture the diversity of all students.

True educational equity demands radical thinking and action. It requires us to embrace intersectionality, not just in our curriculum but in our daily teaching practices. As educators, we must constantly ask ourselves, “Who am I including in my teaching, and who am I leaving out? And crucially, why?” This self-interrogation is vital as it compels us to confront and dismantle our biases.

In a system marred by historical and systemic inequalities, each lesson, each interaction, must be an act of resistance against the prevailing norms of white supremacy. It’s about ensuring that every student, irrespective of their race, religion, or background, feels valued and understood in all classrooms.

Forgiveness and Radical Education: A Path Forward

Ms. Caulkin, wherever you are, whether in this realm or another, I forgive you. I believe what you were really saying was that you were unprepared and ill-equipped to provide what I deserved in your classroom. You probably didn’t intend to exclude me from the education given to my peers but were, to an extent, aware of your discomfort as my teacher. I forgive you, not because your actions were justifiable, but because I understand you were operating within limited constructs and education that hindered you from addressing your discomfort. If you have ever reflected on that moment when you declared yourself unable to serve my educational needs, I hope you have found forgiveness for yourself, as I have done so many times. Your declaration, while painful, ignited in me the spirit of a radical educator. It instilled resilience and forged a fighter within me, surpassing any academic lesson you might have imparted.